In a dilute gas, the thermal motion of atoms or molecules simply increases in amplitude as the temperature increases. The kinetic theory of gases explains the relationship between pressure and temperature in terms of the momentum transferred from gas molecules onto the walls of a containing vessel. In a crystal lattice (or, for that matter, any other condensed phase) the thermal motion of atoms is constrained by the presence of neighbouring atoms. This is a consequence of the fact that the atoms move within the confines of the lattice potential generated by the neighbouring atoms.

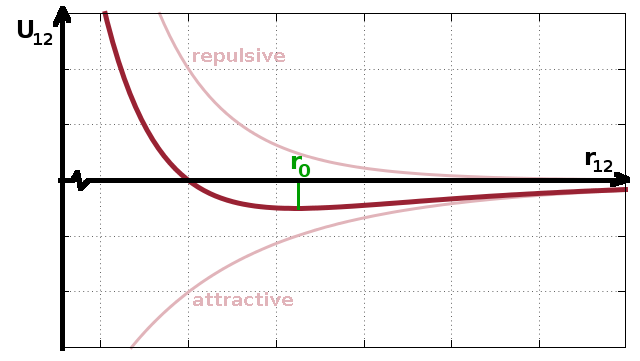

Interatomic potentials comprise a repulsive term and an attractive term resulting from the repulsion of like charges (electron clouds) and the attraction of dipole moments (van der Waals force). In the case of the Lennard-Jones potential (Fig.), this is characterised by an $r^{-12}$ repulsive term and a $-r^{-6}$ attractive term. Other potentials used in computational studies use different formulae representing roughly the same functional behaviour: the repulsive term decreases much faster with interatomic distance, $r_{12}$, than the attractive component. The result is a very steep potential barrier when a probe atom moves into the potential surrounding another atom and a much more gradual asymptotic increase in potential energy as the probe atom is pulled away from the equilibrium distance, $r_0$, located at the minimum of the potential.

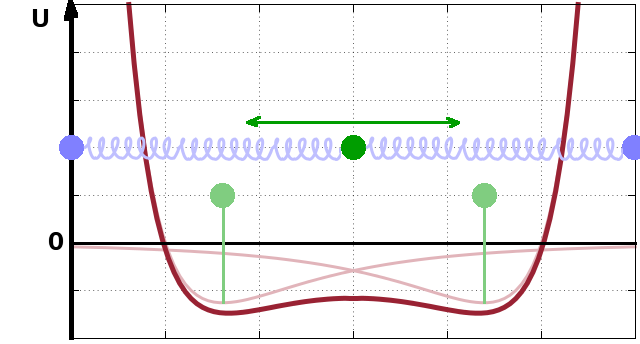

In a crystal, each atom is surrounded by a potential of this type. All the potentials add up, and their asymptotic tails overlap, forming broad but shallow wells between them. The equiilibrium position, $r_0$, of an atom within such a potential well generated by its neighbours is shifted slightly relative to the equilibrium distance in a dilute system, but because the well is very shallow, the probe atom (dark green) can oscillate freely within the well while being strongly confined by the repulsive terms of its neighbours' potentials. This gives rise to the notion of chemical bonds as springs connecting masses (atoms), where the eigenfrequencies of the springs are determined by the spring constant and the mass of the atoms. Of course there is nothing special about the atom shown at the centre - each atom is enclosed by a potential made up of its neighbours in exactly the same way.

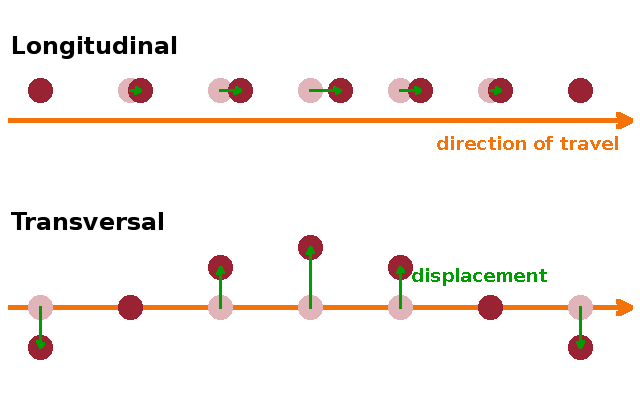

In a one-dimensional crystal (i.e. a linear chain of atoms), a wave can only travel along the one axis present - forward or backward, but not off axis. However, the individual atoms can move either along the direction of propagation of the wave or perpendicular to it. In a longitudinal wave, the atoms move backwards and forwards along the wave vector when the wave reaches them, but the chain remains a straight line. On the other hand, a transversal wave leaves the atoms in their original positions along the chain (like in a necklace where the individual beads are locked in place by knots) but allows them to move sideways. This corresponds to a wave of the string tying the beads together rather than the beads themselves. The distinguishing feature between the two types of wave is therefore the relative direction of the wave vector (shown in orange) and the displacement vector (green) of the atoms.

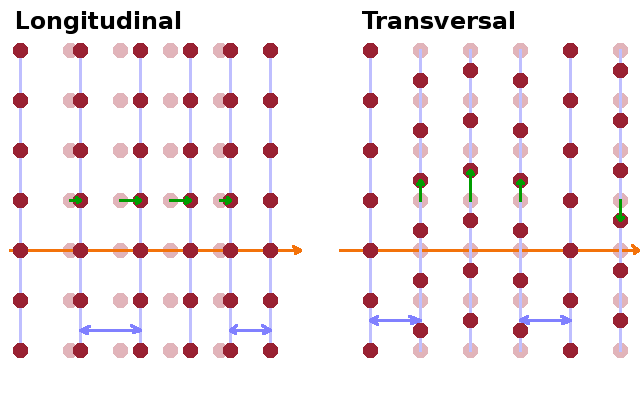

In a three-dimensional crystal, it is whole lattice planes that oscillate instead of individual atoms. As in the linear chain, a wave can be longitudinal or transversal depending on the direction of displacement relative to the wave vector. In principle, oscillations can occur in any direction within a crystal lattice. However, any oscillation pattern in three dimensions can be interpreted as a linear combination of three waves travelling in three linearly independent directions. Which directions are used for this purpose depends on the crystal structure: In structures where the lattice parameters are different, the lattice vectors are typically used for this purpose. In more symmetric structures such as cubic ones, oscillations along the unit cell vectors would be indistinguishable, so a face (110) and a spatial (111) diagonal and are used alongside one lattice vector (100). There are one longitudinal and two transversal waves for each direction of propagation since the lattice planes can oscillate along the wave vector or in two orthogonal directions within the plane perpendicular to the wave vector.

For longitudinal waves, there is a periodic increase and decrease of the lattice spacing in the direction of propagation of the wave. This manifests itself as transient microstrain and will affect the diffraction line width since the Bragg condition for constructive interference is disrupted due to the change in lattice spacing. On the other hand, transversal waves do not change the lattice spacing in the direction in which the wave travels, so Bragg peaks in this direction are not affected.

The relationship between the frequency of oscillation, $\omega$, and the wave number, $k$ (i.e. the magnitude of the wave vector) is different for the different types of oscillation and for different systems. We will next derive this function, the dispersion relation, for a monatomic chain and a few other model systems and compare the results with those for some real materials.