There are five Bravais lattices in a plane and 14 in three-dimensional space. They represent the distinct ways to fill an area or volume by repeating a single unit cell periodically and without leaving any spaces. All Bravais lattices contain only a single type of lattice point (which, in the case of crystal lattices, represents an atom) - all lattice points are indistinguishable. There are two distinguishing features between Bravais lattices, the symmetry of the unit cell and whether the unit cell is primitive or (body, side, or face) centred, i.e. whether it contains additional lattice points beyond the corner ones.

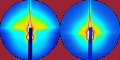

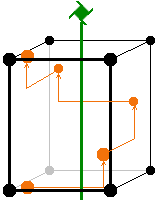

In the case of simple metals, where the structure consists entirely of identical atoms, one of the Bravais lattices would be sufficient to describe the periodic structure. However, in binary compounds (or even more complex ones) such as salts (e.g. NaCl) a Bravais lattice alone isn't sufficient to describe the structure - the second atom type needs to be fitted into the unit cell. As a result, the symmetry of the unit cell may change. In the example, an additional (orange, i.e. different) atom is fitted on the horizontal but not the vertical edges of the cell. Because of the translational symmetry of the lattice, lattice points on an edge of the unit cell have to be repeated on the opposite edge, so the extra atom appears both at the bottom and at the top. The picture shows the symmetry elements in green - in the case of the original lattice, two fourfold axes at the centre and corner of the cell, plenty of mirror lines and a few two-fold rotation axes at the intersection points of the mirrors. Adding the extra atom breaks much of this symmetry: the fourfold axes are reduced to twofold symmetry because they would otherwise reproduce orange atoms on the sides, and the diagonal mirror planes vanish for the same reason.

Note that the extra atom must be different from the existing ones: if they were the same, we could describe the new structure using a different lattice without adding any atoms. In this example, the cell would split in half, and the new unit cell would be a primitive rectangular one.

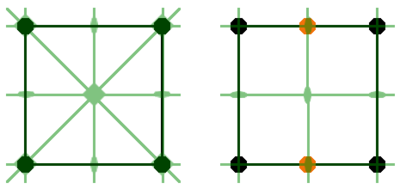

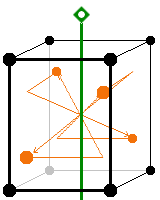

Another cause of symmetry breaking occurs in molecular crystals. Here, each lattice point is occupied by a molecule rather than a (spherical) atom. The low symmetry of the molecule results in much of the symmetry breaking down. The example shows the unit cell of a (hypothetical) cubic ice crystal. Because of the shape of the water molecules occupying each lattice point, all the rotations and most mirror planes will fail, leaving a cell with little internal symmetry. Of course this is just a special case of the situation in the previous example - there are two extra atoms in general positions (positions not coinciding with any symmetry element) in the cell.

Bravais lattice + point group = plane/space group

Because, in general, knowledge of the Bravais lattice alone is insufficient to reconstruct a crystal structure, we need to specify the internal symmetry of the unit cell (its point group) along with the lattice. This combination is known as a plane group (2D) or space group (3D). The word group is meant here in the mathematical sense of a set of symmetry elements and the symmetry operations acting on them. There are 17 plane groups and 230 space groups in total.

| Rotations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-fold rotation point | (no symmetry) | |

| 2 |  |

2-fold rotation point | (180°) |

| 3 |  |

3-fold rotation point | (120°) |

| 4 |  |

4-fold rotation point | (90°) |

| 6 |  |

6-fold rotation point | (60°) |

| Reflections | |||

| m |  |

mirror axis | |

| g |  |

glide axis | (flip & translate by a/2) |

The table lists all symmetry operations in two dimensions, along with their symbols used in the names of symmetry groups and for graphical purposes. All symmetry elements in 2D are based on rotations or reflections. Translations are generally taken care of by the periodicity of the lattice rather than as a symmetry operation internal to the cell. An exception is the glide plane, which combines a reflection with a translation of the reflected object by half a unit cell vector parallel to the glide axis. The one-fold rotation serves no purpose as such; in group theory, each group must have a neutral element (which does nothing). This allows arithmetic to be carried out with the symmetry operations, e.g. turning a three-fold axis three times does exactly nothing - in group theory terms, 3+3+3=1, while 3+3=-3.

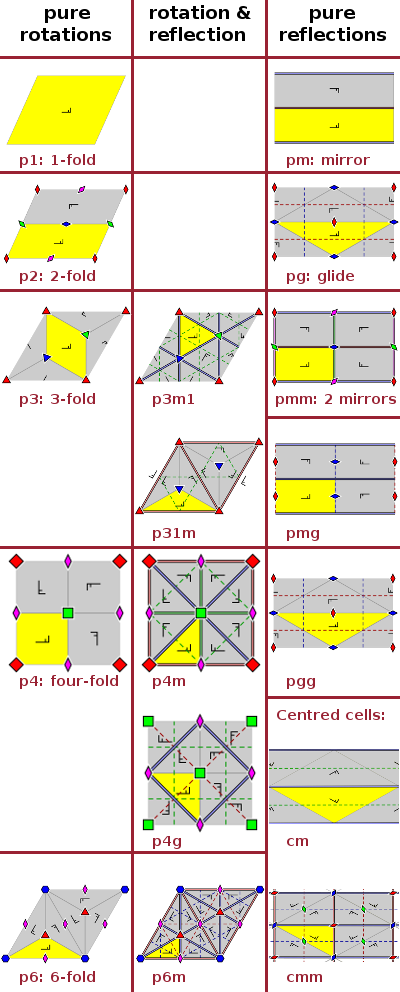

The following table shows the relationships between the 17 plane groups. The individual pictures are taken from the Wikipedia article on Wallpaper groups, which contains many examples of different tilings from architecture, arts and biology which represent these plane groups.

The groups are either based on rotations or reflections (mirror or glide axes) or a mixture of the two. Most are set in primitive cells, but two are based on the centred rectangular Bravais lattice. The table shows the unit cells of each of the 17 groups with their symmetry elements using the standard symbols introduced above. The part of the unit cell highlighted in yellow is known as the asymmetric unit. It is the smallest unit that can be used to build the entire cell by applying the symmetry elements to it. The unit cell itself is the asymmetric unit of the translation operation; when there are other symmetry elements present, the asymmetric unit is smaller than the unit cell. The "letter-F" symbol shown demonstrates how shapes placed in the unit cell are replicated by applying the symmetries. This corresponds to a crystal lattice where points are occupied by molecules rather than (spherical) atoms.

The nomenclature of the groups follows a pattern (the Hermann-Mauguin scheme): The first letter indicates whether the Bravais lattice is primitive (p) or centred (c). This is followed by the predominant symmetry element, i.e. the highest-order rotation (6, 4, 3, 2, or 1). Two intersecting mirror axes always generate a two-fold rotation point, so the '2' symbolising these rotations is usually omitted, and any mirror (m) or glide (g) axes take precedence in these cases. Where necessary to identify a group uniquely, a second symmetry element is specified, which will usually be a mirror or glide plane. Finally, for structures with a threefold axis and a mirror plane, there are two distinct groups depending on whether all rotation points are located on a mirror line or not; these are distinguished, somewhat arbitrarily, by including a 1-fold rotation (i.e. no particular symmetry) as either second or third symmetry element.

Note that most groups contain more symmetry elements than those specified in their Hermann-Mauguin symbol - only as many as needed to describe the structure uniquely are usually listed.

| Rotations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-fold rotation axis | (no symmetry) | |

| 2 |  |

2-fold rotation axis | (180°) |

| 21 |  |

2-fold screw axis | (180° & translate by a/2) |

| 3 |  |

3-fold rotation axis | (120°) |

| 31 |  |

3-fold screw axes | (120° & translate by a/3) |

| 32 |  |

(120° & translate by 2a/3) | |

| 4 |  |

4-fold rotation axis | (90°) |

| 41 |  |

4-fold screw axes | (90° & translate by a/4) |

| 42 |  |

(90° & translate by a/2) | |

| 43 |  |

(90° & translate by 3a/4) | |

| 6 |  |

6-fold rotation axis | (60°) |

| 61 |  |

6-fold screw axes | (60° & translate by a/6) |

| 62 |  |

(60° & translate by a/3) | |

| 63 |  |

(60° & translate by a/2) | |

| 64 |  |

(60° & translate by 2a/3) | |

| 65 |  |

(60° & translate by 5a/6) | |

| Roto-inversions | |||

| 1 |  |

centre of inversion | (point inversion only) |

| 3 |  |

3-fold inversion axis | (120° & inversion) |

| 4 |  |

4-fold inversion axis | (90° & inversion) |

| 6 |  |

6-fold inversion axis | (60° & inversion) |

| Reflections | |||

| m |  |

mirror plane | |

| a,b,c |  |

axial glide planes | (flip & translate by (a,b,c)/2) |

| n |  |

diagonal glides | (flip & translate by half a face diagonal in each direction) |

| d |  |

diamond glides | (flip & translate by a quarter of a face diagonal each) |

In three dimensions, a number of additional symmetry operations arise. First, there are screw axes in addition to the plain rotations we know from the two-dimensional case. A screw axis is a combination of a rotation and a translation along the direction of the axis of rotation. The translation part is a movement along the axis by an integer multiple of steps 1/n of the lattice parameter in length, where n is the order of the rotation. The two operations occur together, i.e. no lattice point is generated at the intermediate position (after the rotation, but before the translation).

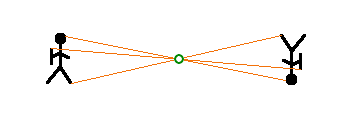

Three-dimensional space also supports inversion at a point (a centre of inversion, above). This is similar to a focal point - all points are mapped to positions directly across the centre, at the same distance. As a result, shaped objects such as molecules are mapped upside-down instead of simply mirrored.

A centre of inversion is a special case of a roto-inversion axis, i.e. a rotation combined with an inversion - in the case of the pure centre of inversion, the rotation axis is just one-fold. A two-fold roto-inversion axis is equivalent to a mirror plane perpendicular to the axis; it is not listed as a separate symmetry element for this reason. Three-, four- and six-fold roto-inversion axes all occur in 3D space and are independent symmetry operations. As was the case with screw axes, an intermediate lattice point (after the rotation, but before the inversion) is not generated.

Some additional possibilities also arise among the reflections: in addition to the axial glide planes corresponding to the glide axis in 2D, there are glide planes with a translation component along all three face diagonals of the unit cell simultaneously, by either a quarter or half of the length of that diagonal.

| number of | 2D | 3D |

|---|---|---|

| Bravais lattices | 5 | 14 |

| point groups | 10 | 32 |

| plane/space groups | 17 | 230 |

As in the 2D case, the symmetry operations are collected in point groups. The number of distinct

groups is again finite - there are now 32. When combined with 14 Bravais lattices, this results

in 230 distinct space groups. Every crystalline material has one of these 230 structures. All

230 space groups are listed in the

International Tables

from the International Union of Crystallography. The Tables show each space group with a graphical

representation of their symmetry elements, special

positions (points located on one or more of the symmetry elements) and general positions (where

a point at x,y,z is repeated within the unit cell due to the symmetry of the structure). Systematic

absences of diffraction lines due to non-primitive lattices or symmetry operations including an

internal translation (glide planes and screw axes) are also shown.

[sample

from the International Tables - see e.g. space group P21/c on p.184]

Having introduced point, plane and space groups, we will make a small detour to see how group theory treats symmetry elements and their relationships.