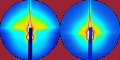

The ideal gas law $$pV_m=RT$$ describes a simple relationship between pressure and (molar) volume on the one hand and the thermal energy of the gas on the other. This idealised equation of state neglects interactions between the individual atoms or molecules of the gas. This is quite reasonable in the dilute limit, but causes problems when atoms encounter each other more frequently. Real gases therefore deviate from the ideal gas law. The extent of the deviation manifests itself in the compression factor $$Z=\frac{pV_m}{RT}\qquad.$$ For an ideal gas, the compression factor is always equal to 1, but for real gases it depends on the pressure. Typically, it decreases at first, then after a sharp minimum rises continuously to values greater than 1. The location of the minimum and the point at which the deviation turns from negative to positive is different for different real gases.

One practical way of adapting the ideal gas law is the virial equation: $$pV_m=RT\left(1+\frac{B}{V_m}+\frac{C}{V_m^2}+\dots\right)$$ It expands the deviation into a series of terms in progressive powers of the inverse molar volume. Each term has a virial coefficient, $B, C, \dots$, which is a (temperature-dependent) material property. While this addresses practical concerns to do with engine design for certain operating gases, it does nothing to help understanding where the deviations come from.

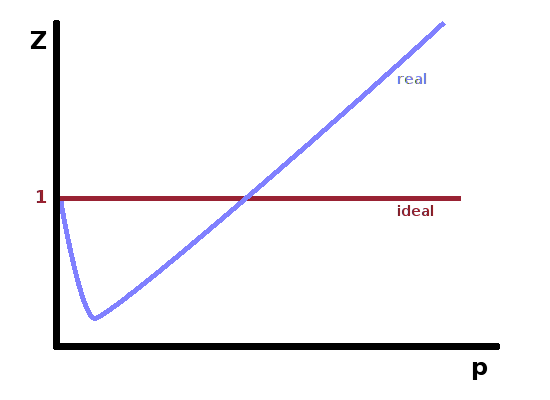

The interatomic forces between nearby atoms generally comprise a repulsive interaction due to the repulsion of the electron clouds of the atoms and a more long-range attractive interaction mainly due to dipoles. This is often described in terms of the Lennard-Jones potential, which has an attractive term proportional to $r^{-6}$ and a repulsive term proportional to $r^{-12}$, although alternative parameterisations exist. Because of the different dependence of both terms on the interatomic distance $r$ there will be a shallow potential minimum corresponding to the equilibrium distance in a condensed system. In a gas, there is too much thermal energy to allow the atoms to settle into this potential minimum, but the repulsive term still prevents them from approaching each other too closely.

The van-der-Waals equation of state takes into account the repulsive and attractive interactions explicitly: $$\left(p+\frac{a}{V_m^2}\right)(V_m-b)=RT\qquad.$$ Compared with the ideal gas law, the molar volume is reduced by a constant known as the excluded volume, $b$, which is interpreted as the volume blocked by the gas atoms or molecules themselves to account for the fact that several atoms cannot occupy the same space and that the atoms make fast random movements about their position as a consequence of their thermal energy. At the same time, the pressure is increased by the internal pressure, $\frac{a}{V_m^2}$. The rationale for this is that the long-range attractive forces are balanced for all gas atoms except for those near the walls of the container since these atoms are lacking gas atoms on one side (facing the wall). As a result, they are pulled into the container, and the effective pressure (force acting on the wall) is reduced accordingly, i.e. the correction term is added to the measured pressure, $p$. The correction scales with $V_m^{-2}$ because the force acting on the affected gas atoms and the number of atoms both depend on the number density ($\propto V_m^{-1}$), combining to the inverse-square relationship.

The van-der-Waals equation is only one parameterisation of the attractive and repulsive interactions. There are other equations of state that address these interactions differently, but they all have two parameters for the two types of interaction. All of them are approximations. Compared to the virial equation, they all have the advantage of describing a simple model based on physical understanding but the disadvantage of greater deviations from observed behaviour for any particular gas.

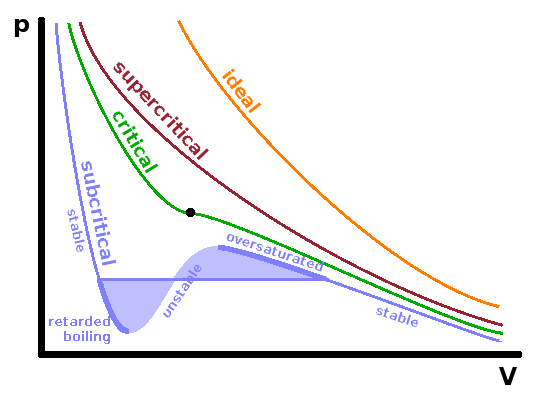

Because of the absence of interatomic interactions, all isotherms of an ideal gas are hyperbolae: $$p(V_m)=\frac{RT}{V_m}$$ In a real gas, supercritical isotherms look fairly similar, except that they have a shallower slope due to the exclusion volume. This deviation is strongest at high pressure and low molar volume. As we have seen when discussing phase diagrams, subcritical isotherms of real gases are very different as they cut through the phase transition region between liquid and gas. The apex of the two-phase region is the critical point, located on the critical isotherm at $T_c$.

An isothermal quasi-static compression process will follow a sub-critical isotherm such as the blue line in the diagram from right to left. As the boundary of the two-phase region is reached, the pressure remains constant (horizontal line in the pV diagram) during further compression as gas is transformed into liquid. At the end of the two-phase region, as no gas is left, the pressure rises sharply with further compression due to the much smaller compressibility of the condensed phase.

If the compression is carried out more quickly, i.e. deviating from quasi-static conditions, it is possible to continue following the isotherm around the edge of the two-phase region up to the local maximum shown in the diagram. The gas is known as oversaturated vapour in this metastable regime. Similarly, when expanding the liquid phase under non-quasistatic conditions, it is possible to continue on the subcritical isotherm to its local minimum, the metastable retarded boiling regime. Within these metastable areas, spontaneous phase change can always occur if a sudden disturbance or the presence of a surface enables the nucleation of the second phase. It is important to note that these metastable conditions are deviations from thermodynamic equilibrium, a concept which assumes all changes to be quasi-static. The unstable region of the isotherm between its local minimum and its local maximum is totally inaccessible since it would mean that an increase in pressure would result in an expansion of the medium, which is clearly unphysical.

We can use the van-der-Waals equation $$\left(p+\frac{a}{V_m^2}\right)(V_m-b)=RT$$ to estimate the critical parameters of a real gas considering that the critical point is a point of inflection of the critical isotherm. By re-writing the van-der-Waals equation in terms of pressure as a function of (molar) volume, $$p(V_m)=\frac{RT}{V_m-b}-\frac{a}{V_m^2}\qquad,$$ we can take the first and second derivative of the critical isotherm and find the inflection point by forcing them both to zero. (The first derivative must be zero for minima, maxima and inflections, i.e. the slope at all these points is horizontal. The second derivative determines whether the direction of the slope changes or, in the case of an inflection point, stays the same on either side.) Therefore, $$\left.\frac{{\rm d}p}{{\rm d}V_m}\right|_{T=T_c}=-\frac{RT_c}{(V_{m,c}-b)^2}+\frac{2a}{V_{m,c}^3}\overset{!}{=}0$$ and $$\left.\frac{{\rm d}^2p}{{\rm d}V_m^2}\right|_{T=T_c}=\frac{2RT_c}{(V_{m,c}-b)^3}-\frac{6a}{V_{m,c}^4}\overset{!}{=}0\qquad.$$ This produces two simultaneous equations: $$\left\{\begin{array}{lll} RT_cV_{m,c}^3&=&2a(V_{m,c}-b)^2\\ 2RT_cV_{m,c}^4&=&6a(V_{m,c}-b)^3 \end{array}\right\}\qquad,$$ which can be divided by one another, conveniently removing the higher powers: $$2V_{m,c}=3(V_{m,c}-b)\qquad.$$ This is solved for the critical molar volume: $$V_{m,c}=3b$$ By substituting that back into one of the two simultaneous equations, we get $$RT_c(3b)^3=2a(3b-b)^2$$ and solve for the critical temperature: $$T_c=\frac{8ab^2}{27Rb^3}=\frac{8a}{27Rb}\qquad.$$ Both $T_c$ and $V_{m,c}$ can be substituted back into the van-der-Waals equation, giving a solution for the critical pressure: $$p_c=\frac{RT_c}{V_{m,c}-b}-\frac{a}{V_{m,c}^2}=\frac{R8a}{27Rb(3b-b)}-\frac{a}{9b^2}=\frac{4a}{27b^2}-\frac{a}{9b^2}=\frac{a}{27b^2}\qquad.$$ Now that all critical variables are expressed in terms of the van-der-Waals parameters, internal pressure coefficient $a$ and excluded volume $b$, it is possible to normalise all state variables anywhere in the $pVT$ cube to these critical values and introduce a set of reduced variables: $$p_r=\frac{p}{p_c},\qquad T_r=\frac{T}{T_c},\qquad V_{m,r}=\frac{V_m}{V_{m,c}}\qquad.$$ As long as a real gas is adequately described by the van-der-Waals model, the theorem of corresponding states maintains that the behaviour of any real gas should be the same in terms of these reduced variables. For example, the critical compression factor can be reduced to a simple number valid for all van-der-Waals gases: $$Z_c=\frac{p_cV_{m,c}}{k_BT_c}=\frac{3}{8}\qquad.$$

It may be useful to compare the van-der-Waals and virial equations to backfill the virial equation with a model of the physical effects causing the behaviour it describes. To do this, we need to bring the van-der-Waals equation into the shape of the virial equation, a series of powers of $\frac{1}{V_m}$: $$p=\frac{RT}{V_m-b}-\frac{a}{V_m^2}=\frac{RT}{V_m(1-\frac{b}{V_m})}-\frac{a}{V_m^2}\qquad.$$ The bracket can be expanded into a series according to $$\frac{1}{1-x}=1+x+x^2+\dots\qquad(\textrm{for}\,x\lt 1)\qquad:$$ $$p=\frac{RT}{V_m}\left(1+\frac{b}{V_m}+\frac{b^2}{V_m^2}+\dots\right)-\frac{a}{V_m^2}\qquad.$$ Bring one $V_m$ over to the left to match the left-hand side of the virial equation: $$pV_m=RT\left(1+\frac{b}{V_m}+\frac{b^2}{V_m^2}+\dots\right)-\frac{a}{V_m}=RT\left(1+\frac{b-\frac{a}{RT}}{V_m}+\frac{b^2}{V_m^2}+\dots\right)$$ By comparison with the virial equation, $$pV_m=RT\left(1+\frac{B}{V_m}+\frac{C}{V_m^2}+\dots\right)\qquad,$$ it is clear that we can express the virial coefficients in terms of the van-der-Waals parameters: $$B=b-\frac{a}{RT}\qquad\textrm{and}\qquad C=b^2\qquad.$$ The Boyle temperature is the temperature at which a real gas behaves almost like an ideal gas for an extended range of pressures by virtue of the fact that the second virial coefficient is zero: $$B=b-\frac{a}{RT_{Boyle}}\overset{!}{=}0\qquad.$$ By solving this for the temperature, we can see that any van-der-Waals gas will behave like an ideal gas at one specific multiple of its critical temperature: $$T_{Boyle}=\frac{a}{bR}=\frac{27T_c}{8}\qquad.$$

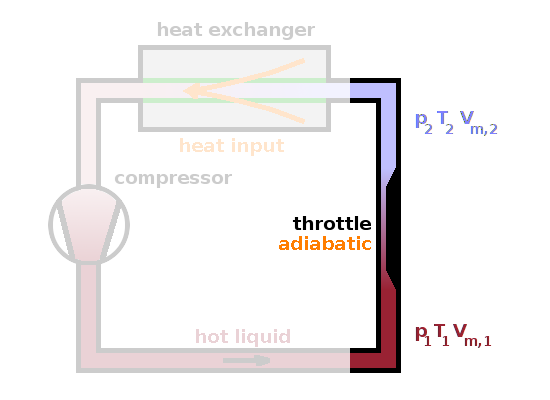

An example where real gases show different behaviour from an ideal gas is the Joule-Kelvin effect (or Joule-Thomson effect). When introducing enthalpy in the context of thermodynamic engines, we have encountered the adiabatic throttle, i.e. a well-insulated obstruction in a pipe through which a warm gas flows. This is used in refrigerators because the throttling process absorbs heat, and if confined in an adiabatic enclosure, that heat has to come from the operating gas. We'll concentrate here on the throttle itself; the remainder of the refrigerator circuit is immaterial here.

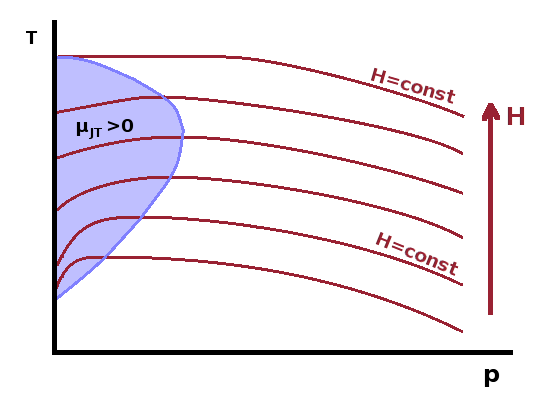

The temperature change during throttling is calculated by expressing the temperature as a state function depending on two other state variables, in this case pressure and enthalpy: $$T=T(p,H)\qquad.$$ The total differential of the temperature is the sum of its change with each of the variables multiplied by the change in that variable: $${\rm d}T=\left.\frac{\partial T}{\partial p}\right|_H{\rm d}p+\left.\frac{\partial T}{\partial H}\right|_p\color{red}{\cancel{\color{black}{{\rm d}H}}^0}\qquad.$$ Since the throttle is adiabatic, there is no enthalpy change, ${\rm d}H=0$, so only the first term survives. The partial derivative in it, the isenthalpic temperature change with pressure, is known as the Joule-Kelvin (or Joule-Thomson) coefficient, $$\mu_{JK}=\left.\frac{\partial T}{\partial p}\right|_H\qquad.$$ Clearly, a refrigerator will only work if the Joule-Kelvin coefficient is positive, i.e. the gas cools down as the pressure decreases upon expansion. To calculate the Joule-Kelvin coefficient, we can apply the cyclic rule of differentiation, which states that for three interdependent variables, the product of the three partial derivatives is -1 if the derivatives are cycled through the three permutations: $$\left.\frac{\partial x}{\partial y}\right|_z\left.\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}\right|_y\left.\frac{\partial y}{\partial z}\right|_x=-1\qquad.$$ This is a variation on the chain rule for a cyclic relationship between variables. Applied to the Joule-Kelvin coefficient, it yields $$\mu_{JK}=\left.\frac{\partial T}{\partial p}\right|_H=-\left.\frac{\partial H}{\partial p}\right|_T\left.\frac{\partial T}{\partial H}\right|_p= -\left.\frac{\partial H}{\partial p}\right|_T\frac{1}{c_p}\qquad,$$ where the heat capacity, $c_p=\left.\frac{\partial H}{\partial T}\right|_p$, has been substituted for the second differential on the right-hand side. Since the differential form of the enthalpy is $${\rm d}H=T{\rm d}S+V{\rm d}p\qquad,$$ we can work out the first differential by multiplying ${\rm d}p$ across - the temperature has to be kept constant because otherwise the chain rule would have to be invoked: $$\left.\frac{\partial H}{\partial p}\right|_T=T\left.\frac{\partial S}{\partial p}\right|_T+V=-T\left.\frac{\partial V}{\partial T}\right|_p+V,$$ where one of the Maxwell relations is used to substitute the entropy differential with something more tangible. This relationship goes back into the equation for the Joule-Kelvin coefficient, giving $$\mu_{JK}=\frac{1}{c_p}\left(T\left.\frac{\partial V}{\partial T}\right|_p-V\right)\qquad.$$ Since the heat capacity, (absolute) temperature, thermal expansion coefficient and molar volume are all always positive, the relative size of the two terms in the bracket determines whether we have a viable refrigerator.

For an ideal gas, the Joule-Kelvin coefficient is easily calculated: We can rearrange the ideal gas law for the molar volume, $$V_m=\frac{RT}{p}\qquad,$$ and calculate its change with temperature, $$\frac{\partial V_m}{\partial T}=\frac{R}{p}\qquad.$$ Substituting both into the equation for the Joule-Kelvin coefficient, we have $$\mu_{JK}=\frac{T\left.\frac{\partial V_m}{\partial T}\right|_p-V_m}{c_p}=\frac{T\frac{R}{p}-\frac{RT}{p}}{c_p}=0\qquad.$$

Therefore, a refrigerator wouldn't work if the operating medium was an ideal gas. At least the ideal gas wouldn't do any harm and heat up the fridge - something which can happen with a real gas as operating medium if $$V_m\gt T\left.\frac{\partial V_m}{\partial T}\right|_p\qquad\textrm{or}\qquad\alpha T\lt 1\qquad,$$ where $\alpha$ is the volume expansion coefficient, $\alpha=\frac{1}{V}\frac{\partial V}{\partial T}$. This is the reason why helium cryostats, often used for experiments at very low temperatures, cannot be used at room temperature.

So far, we have limited ourselves to systems comprising only a single component and have considered thermal equilibrium exclusively in terms of the relationships between the various phases of that component. Next, we will be introducing a formalism to describe thermodynamic equilibrium in mixtures.